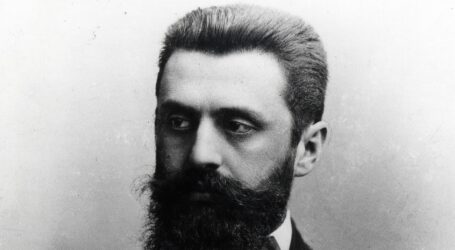

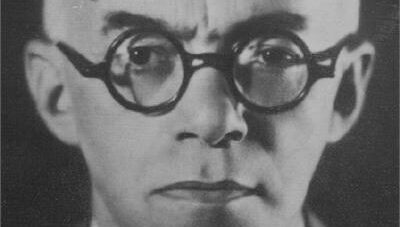

Ze’ev Jabotinsky: Biography

Ze’ev Jabotinsky

Born: October 17, 1880;

Died: August 3, 1940, Hunter

Ze’ev Jabotinsky born Vladimir Jabotinsky was a founder of the Revisionist Zionist movement, founder of the Beitar Youth Movement, and founder of the political party Hatzohar which would go on to merged into Herut and later Likud political party which as of 2024 currently the majority of seats in the Israeli Parliament the Knesset.

Vladimir Jabotinsky was born in Odessa in 1880. He began his professional career by working as a journalist where he began to espouse Zionist views. He would travel through Europe for many years throughout this time. He became such a popular journalist that he would go on to join his paper’s editorial staff in Odessa. He created Jewish self-defense militias resulting from a pogrom of Jews in April 1903. He would serve as a delegate in the Sixth Zionist Congress which had on the agenda a vote for the Uganda Scheme, the British Government’s scheme for Jewish settlement in Africa which Jabotinsky would vote against. During World War I, Jabotinsky pushed the British Government to establish a Jewish Legion which they would eventually do in 1917. He fought with the Jewish Legion against the Ottoman Empire in Palestine. He trained Jews in British Palestine in the use of weapons and was arrested by the British and sentenced to prison, but public outcry against the verdict resulted in his amnesty.

He would go on to found the Beitar Youth Movement in 1923 as well as other organizations like the political party Hatzohar which advocated “establishment of a self-governing Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan under the auspices of a Jewish majority.” This was in sharp contrast to the socialist Labor Zionism of David Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel who would refer to him as “Vladimir Hitler.”. Jabotinsky would go on to resign from the World Zionist Organization and would found the New Zionist Organization which followed his political views of establishing a Jewish states on both sides of the Jordan and not restricting Jewish immigration to the land. He would testify before the 1937 Palestine Royal Commission also called the Peel Commission in which he espoused these views which contrasted with the Labor Zionists who accepted albeit reluctantly the partitioning of the land.

He would publish many stories, books, poems, and essays throughout his life. During World War II, he also supported the raising of a Jewish Army in order to fight Nazi Germany. He would die in August 3, 1940 in Hunter, New York.

One of his most well-known essays is the Iron Wall essay. In this essay he espouses much of his political thought.

In this essay he writes about how he is not an “enemy of the Arabs” as he is reputed to being, saying that as long as Jews maintain the majority in the land he will happily give “equality of rights.”

I am reputed to be an enemy of the Arabs, who wants to have them ejected from Palestine, and so forth. It is not true.

Emotionally, my attitude to the Arabs is the same as to all other nations – polite indifference. Politically, my attitude is determined by two principles. First of all, I consider it utterly impossible to eject the Arabs from Palestine. There will always be two nations in Palestine – which is good enough for me, provided the Jews become the majority. And secondly, I belong to the group that once drew up the Helsingfors Programme , the programme of national rights for all nationalities living in the same State. In drawing up that programme, we had in mind not only the Jews, but all nations everywhere, and its basis is equality of rights.

When discussing a “voluntary agreement” between the Jews and the Arabs, he rejects the Labor Zionist view that there can be an agreement with the Arabs on the establishment of a country with a Jewish majority. He goes on to discuss the history of colonization in other countries and says that:

The native populations, civilised or uncivilised, have always stubbornly resisted the colonists, irrespective of whether they were civilised or savage.

In 1902, Theodor Herzl wrote a utopian novel titled Altneuland in which he depicts a utopian vision of Palestine where it is flourishing and thriving with new technologies and equal rights between Arabs and Jews in a Jewish state. This was a reflection of the Labor Zionist political philosophy based on ideas such as progress and technological development, and that Arabs would happily share in this without any pushback against the Jewish state. Jabotinsky rejects this philosophy saying that:

This is equally true of the Arabs. Our Peace-mongers are trying to persuade us that the Arabs are either fools, whom we can deceive by masking our real aims, or that they are corrupt and can be bribed to abandon to us their claim to priority in Palestine , in return for cultural and economic advantages. I repudiate this conception of the Palestinian Arabs. Culturally they are five hundred years behind us, they have neither our endurance nor our determination; but they are just as good psychologists as we are, and their minds have been sharpened like ours by centuries of fine-spun logomachy. We may tell them whatever we like about the innocence of our aims, watering them down and sweetening them with honeyed words to make them palatable, but they know what we want, as well as we know what they do not want. They feel at least the same instinctive jealous love of Palestine, as the old Aztecs felt for ancient Mexico, and the Sioux for their rolling Prairies.

He finishes his essay invoking his idea of an “Iron Wall”:

Zionist colonisation must either stop, or else proceed regardless of the native population. Which means that it can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population – behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.

That is our Arab policy; not what we should be, but what it actually is, whether we admit it or not. What need, otherwise, of the Balfour Declaration? Or of the Mandate? Their value to us is that outside Power has undertaken to create in the country such conditions of administration and security that if the native population should desire to hinder our work, they will find it impossible.

He finishes this essay by proclaiming that Zionism is moral and just and discussing an eventual agreement with the “Palestine Arabs.”

In the second place, this does not mean that there cannot be any agreement with the Palestine Arabs. What is impossible is a voluntary agreement. As long as the Arabs feel that there is the least hope of getting rid of us, they will refuse to give up this hope in return for either kind words or for bread and butter, because they are not a rabble, but a living people. And when a living people yields in matters of such a vital character it is only when there is no longer any hope of getting rid of us, because they can make no breach in the iron wall. Not till then will they drop their extremist leaders, whose watchword is “Never!” And the leadership will pass to the moderate groups, who will approach us with a proposal that we should both agree to mutual concessions. Then we may expect them to discuss honestly practical questions, such as a guarantee against Arab displacement, or equal rights for Arab citizen, or Arab national integrity.

Sources: