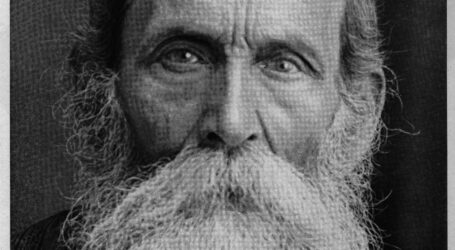

Antoun Saadeh: Biography

Born: March 1, 1904, Dhour El Choueir, Mount Lebanon.

Died: July 8, 1949, Beirut, Lebanon.

Antoun Saadeh was born on March 1, 1904, in the town of Dhour El Choueir in Mount Lebanon. His father, Dr. Khalil Saadeh, was a skilled physician and linguist, and he authored the first English-Arabic dictionary. Meanwhile, his mother, Mrs. Naifeh Nassir, was raised and educated in the United States.

Initially, Antoun Saadeh received his education at one of the Syrian community schools in Cairo. After his mother’s death in 1913, he returned to Lebanon under the care of his grandmother and uncles. With the outbreak of World War I, Saadeh faced difficult circumstances. At just ten years old, he was forced to take responsibility for caring for his younger siblings during this period. He and his siblings joined an orphanage in Brummana for women and children, where they spent the war years.

Antoun Saadeh was a thinker and political leader from Lebanon. He founded the Syrian Social Nationalist Party in 1932. His dream was to unify the Syrian nation by eliminating sectarianism and the divisions imposed by colonialism. Growing up in a diverse cultural environment helped him develop his ideas and social and political vision.

He began his political career in exile, where he contributed to newspaper editing and discussed issues of independence and national unity. In 1922 and 1923, he published articles on Syria’s independence and social issues. However, the pressure of work forced him to halt the daily newspaper and reissue his previous magazine in Argentina, through which his nationalist and revivalist inclinations became evident.

In 1926, Antoun Saadeh founded the “Syrian National League,” but it failed due to weak organization and limited public activities. He then established the “Liberal Nationalists” party in Brazil in 1927, which met a similar fate. After the magazine ceased publication that same year, he turned to working in governmental educational committees.

He founded a structured Syrian movement that focused on Syria’s national affairs and the destiny of the Syrian nation. The party began as a secret organization targeting youth and called for the principles of Syrian nationalism, the separation of religion from the state, and the establishment of a modern state based on national unity and territorial belonging, free from sectarian divisions. Despite political persecution for his positions, Saadeh remained committed to his cause and became a central figure in popular circles. After years in exile, he returned to Lebanon but faced increasing governmental pressure. In 1949, he was executed following a swift trial. Despite this tragic end, his ideas remained a symbol of struggle and sacrifice for the values he believed in.

Saadeh’s book, “The Genesis of Nations,” is a scientific social study focusing on defining the nation and explaining how it emerges and develops within the framework of human interaction with the environment and history. Saadeh believed that a nation is a social entity that arises through multiple factors, such as geographical environment and shared historical experiences, and that it surpasses superficial concepts like race or religion. He clarified that he had written his book in two parts with a clear objective. The first part discusses “the definition of a nation, how it emerges, its place in human development, and its relationship with social phenomena.” The second part addresses “the emergence of the Syrian nation, its relationship with other nations, and its connection to broader historical trends.”

Antoun Saadeh distinguished between the religious and scientific approaches to interpreting the emergence of the human species. He considered the religious approach based on myths and interpretations related to independent creation, while the scientific approach relies on research, experimentation, logic, and analysis to study the evolution of life and organisms. He preferred the scientific method for explaining human origins because it is based on logical foundations and material facts. He pointed out that science has revealed the interconnections among organisms in the evolutionary chain of life. Despite his criticism of religious interpretations, he did not deny the importance of religion and its impact on human life. However, he called for a clear distinction between scientific study and religious interpretations. He argued that the question, “Where did humans come from?” cannot be answered within a strictly scientific framework that encompasses the overall emergence of life, reflecting his realistic and rational stance on intellectual issues.

Saadeh focused on the interaction between social forces and civil rights in society, emphasizing that these rights are not a product of state intervention but arise from social forces such as religion and customs, which help ensure societal stability. He believed that no clear boundaries could be drawn between the stages of cultural evolution. In the early stages of state formation, reliance was placed on the totemic system, a social and cultural framework distinguishing tribes and clans. As society evolved, new structures emerged, such as tribal authority represented by the sheikh or emir. The decline of the totemic system and the rise of an emirate-based structure reflected a transformation in governance, where actual authority became centralized, and public assemblies lost significance.

Antoun Saadeh was arrested three times during his political career, between 1935 and 1949. In 1935, he was arrested for founding the Syrian Social Nationalist Party and sentenced to six months in prison. After his release in May 1936, he was arrested again in June 1936 due to the party’s growing activities and remained imprisoned until November of the same year. He was arrested for the third time in March 1937 after an incident in Bikfaya during a party celebration and was detained until May 1937. In 1938, he was exiled to Argentina due to his political opposition to the Lebanese authorities.

On July 6, 1949, he was arrested after the party declared a revolt against the Lebanese government. He was handed over to the Lebanese authorities and brought to Beirut on July 7. During a rapid trial, he defended himself, but the court refused to delay the ruling. He was executed in the early hours of July 8, 1949, without being allowed to see his family. Despite the secrecy surrounding his trial, his courage and steadfastness in his final moments made him a symbol in modern Syrian history.