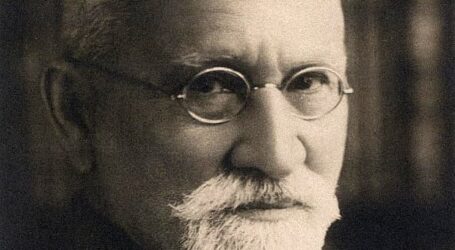

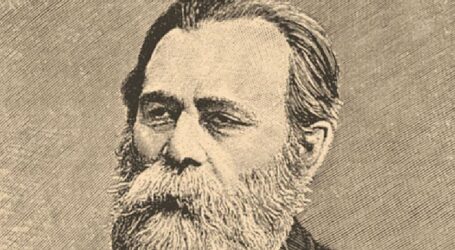

Ahad Ha’am: Biography

Ahad Ha’am

Born: August 18, 1856;

Died: January 2, 1927, Tel Aviv

Ahad Ha’am born Asher Hirsch Ginsberg was a Hebrew journalist and essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zionist thinkers. He is known as the founder of cultural Zionism.

Ahad Ha’am stated that the Jews and Judaism emerged from the “ghetto” at a time when the Jewish religion had become a real burden. The “People of the Book” had become enslaved by the Book itself, to the extent that this very Book weakened and destroyed all creative and emotional capacities among the Jews. The law had turned into a rigid written code, halting Jewish development, obliterating their internal world entirely, and leaving them culturally paralyzed. Hence, the question arose: Can the Jews be normalized, and can the Jewish spirit be liberated from its shackles to reintegrate into the flow of human life without losing its Jewish identity and unique character?

According to Ahad Ha’am, the Jewish question takes two forms: one in the East and the other in the West. In the West, the Jewish question succeeded in liberating the Jews but at the cost of their Jewish identity. It also subjected them to antisemitism, which drove them back into their Jewish world—not out of love for it, but as an escape from hostility. Upon their return, however, they found the Jewish world too narrow to satisfy their cultural needs. This Jewish world was no longer part of their culture (they were Jews who were no longer Jewish). Thus, they aspired to establish a Jewish state where they could live a life resembling that of others, achieving everything they desired but could not attain in their current reality. Even if they did not settle in this state themselves, its mere existence would enhance their status wherever they were, as they would no longer be seen as dependents reliant on the hospitality of the local population.

In contrast, the Jews of the East faced a twofold problem: material and cultural. However, Herzl’s envisioned state would solve neither of these issues, as it paid no attention to the cultural aspect. Regarding the material issue, Ahad Ha’am saw it as impossible to evacuate all surplus Jews from Europe, as the Jewish state could only accommodate a portion of them in Palestine. Thus, solving the problem in its entirety was impossible, and reliance on other proposed solutions (such as increasing the number of Jewish farmers and manual workers) remained essential. Ultimately, resolving the material issue would depend on the economic conditions and cultural levels of the various nations with Jewish minorities.

If the proposed solutions were ineffective and bound to fail, what was the alternative? Ahad Ha’am found the remedy in the problem itself—organically rooted nationalism after its Judaization. He argued that Jewish religion, despite its stagnation, was better suited for modernization than any other religion. It was a rational, collective faith emphasizing reason and community (unlike Christianity, which emphasizes faith and individuality). The monotheistic belief, in his view, was fundamentally an early recognition of the unity of nature and the concept of scientific laws and knowledge that transcend direct perception. (Ahad Ha’am referred here to a cosmic monism.) He noted that the Pharisees, who shaped rabbinic Judaism, rejected both the Essenes (advocates of the spirit) and the Sadducees (advocates of materialism), merging the two by replacing dualism with a holistic cosmic monism rooted in ancient pagan worship and modern secularism. This, he claimed, was the great achievement of “Yavneh” and the reason Judaism had endured through the ages.

However, this did not imply a return to religion, as Ahad Ha’am himself was an atheist. When he visited Palestine and saw the stones of the Western Wall, he felt no religious stirrings but saw it instead as a symbol of the ruin that had befallen the Jewish people. For him, religion was merely a form of expression for the eternal Jewish national spirit embodied in history. It was a vessel rooted in the self, not an absolute external standard. Judaism was a set of Jewish ideas deeply entrenched in Jewish nature or history. Hence, the return must be to this absolute and this alone—the Jewish ethnic self, the source of Judaism, which would replace it and be sanctified, much like the proponents of organic nationalism in Germany and Eastern Europe had done. Ahad Ha’am, influenced by thinkers like Hegel, Herder, and Slavic and German intellectuals, viewed ethnicity as an absolute value in itself. This stood in stark contrast to traditional Jewish religious heritage. For instance, Saadia Gaon stated that the Jews existed for the Torah or because of it, making the people a tool. In contrast, Ahad Ha’am saw everything, including religion, as a tool to affirm the identity of the people.

Ahad Ha’am observed a growing tendency toward organic nationalism among the Jews of Eastern Europe. Hebrew was no longer merely the sacred tongue but became a language for secular Hebrew literature, beginning to replace religion as a unifying framework. He himself contributed to this movement, secularizing religious concepts like the “Chosen People,” transforming it into a Nietzschean term—“Supernation” or “Superior Nation”—that exalted strength and will.

Building on these organic concepts, Ahad Ha’am proposed his theory of “Cultural Zionism,” aiming to revive or modernize traditional Jewish culture to adapt to the modern age within the framework of organic nationalism. He suggested establishing a cultural center in Palestine before founding a Jewish state. This center would act as an organic nucleus for the Jewish “folk” (or organic people), allowing Jewish identity to affirm itself on modern foundations. In Palestine, Jews could settle and engage in various fields of life, from agriculture and manual labor to natural sciences. Over time, such a center would become a hub for the nation, enabling its spirit to manifest and develop toward its highest potential independently. This center would radiate the organic Jewish national spirit to Jewish communities worldwide, revitalizing them, strengthening their national consciousness, and solidifying their unity. From this center, a new Jewish personality—proud of its identity—would emerge, free of the impurities acquired through long years of diaspora.

However, this organic revival would not happen all at once through a simple political process. It was a slow cultural process, akin to organic growth. Ahad Ha’am did not oppose establishing a Jewish state in Palestine with a Jewish majority, but he viewed the state as the culmination of the organic growth process—the final fruit rather than the seed. The cultural center would nurture individuals in the Land of Israel capable of founding a state when the time was ripe—not a Jewish state, but a Judaic state in a secular, holistic sense; a Hebrew secular state. In this framework, the state was not an end in itself but a means to express national identity—a product of slow cultural development rather than a sudden political upheaval.