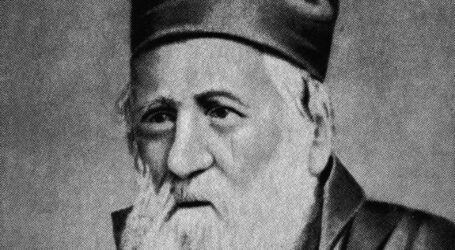

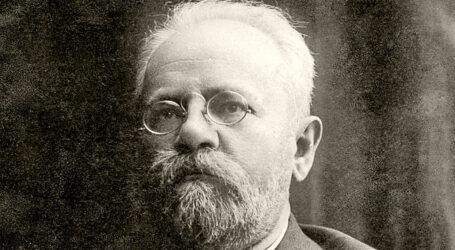

Moses Hess: Biography

Moses Hess

Born: January 21, 1812, Bonn;

Died: April 6, 1875, Paris

Moses Hess, also known as Moritz Hess was born on January 21, 1812 in Bonn, Germany.1 His father was an Orthodox Jew who worked as a merchant. Matrilineally, Hess descended from a long line of Jewish Rabbis and scholars. Hess received a traditional Orthodox Jewish education by his parents, and later his grandfather when he was placed in his custody after his parents moved to Cologne. At 18 years of age, Hess matriculated at the University of Bonn in 1830, of which he never graduated. Hess would work as a teacher and in his father’s business. In 1840, Hess married a Christian girl, Sybille. He would suffer a falling out with his father and would never meet with him again.

In 1837, Moses Hess published The Sacred History of Humanity, in this work he developed his own Philosophy of History, a “combined product of Spinozism and Hegelianism.”2 Hess was actively involved in the socialist movement of his time, even contributing to all the socialist publications. For one publication, called Rhinelander Gazette, Hess served as a correspondent in Paris. Karl Marx would later join him and was influenced by Hess’ thinking, even working with him on some works. However, they would later have a public falling out, with Marx even mocking Hess in his Communist Manifesto.3 While Hess lived in Paris in 1852-1860, he would pursue study in ethnology where he became convinced that Cosmopolitanism was not scientifically sound. Cosmopolitanism “preaches the abolition of national landmarks and the fusing of humanity into one motley mass.”4 Hess believed that humanity consists of different nations each with distinctive physical and mental characteristics. This study brought him to thinking about his own people, the Jews. He would later say that he never entirely forgot about the Jewish people, but became diverted temporarily to something he thought was more important, the working masses of Europe.

Rome and Jerusalem would be Moses Hess’ magnum opus. Upon publishing this book, Hess didn’t receive any recognition for this book from intellectuals of his time, but it was a jolt to German Jews. In his magnum opus, Hess wrote “a preface, twelve letters written to a bereaved lady [a friend of Hess, this form of writing was common in political treatises], an epilogue, and ten supplementary notes. It deals with a wide variety of aspects of the same central subject – the Jews, what they are, and what they should be.”5 Among his many ideas espoused in his work, was that nations are real. Nations are like families, they are real, natural, and historical. Jews won’t be respected as long as they deny their own nationality. He also rejects assimilation as a solution. Hess says that some Jews might seek reform, conversion to Christianity, or education as a means of entering German society but that will not work. He states that “every living, acting people, like every acting individual, has its special field. Indeed, every man, every member of the historical nations, is a political, or as we say at present, a social animal; yet within this sphere of the common social world, there are special places reserved by Nature for individuals according to their particular calling“6 Hess also says that “in exile, the Jewish people cannot be regenerated.”7 Hess says “a common, native soil is a primary condition… the social man, just as the social plant and animal, needs for his growth and development a wide, free soil; without it, he sinks to the status of parasite, which feeds at the expense of others.”8

Hess tells a story in which his grandfather would show him olives and dates, saying that he “remarked, with beaming eyes, ‘these were raised in Eretz Yisroel [Land of Israel]’ Everything that reminds the pious Jew of Palestine is as dear to him as the sacred relics of his ancestral house.”9 Hess talks about the custom of religious Jews putting a bag of dirt from the Holy Land into their grave, and he also talks about Jewish holidays. His argument in invoking these customs and traditions is that they all “have their origin in the patriotism of the Jewish nation.”10 Hess criticized “the ‘new’ Jew, who denies the existence of the Jewish nationality, is not only a deserter in the religious sense, but is also a traitor to his people, his race and even to his family.”11

Looking towards the future, Hess says that “what we have to do for regeneration of the Jewish nation is, first, to keep alive the hope of the political rebirth of our people, and next, to reawaken that hope when it slumbers. When political conditions in the Orient shape themselves so as to permit the organization of a Jewish State, this beginning will express itself in the founding of Jewish colonies in the land of their ancestors, to which enterprise France will undoubtedly lend a hand.”12 Hess says that France will play a role because, among other reasons, how big a proportion of philanthropic funds the Jews made toward Syrian war victims. Hess called France a “savior who will restore our people to its place in universal history.”13

Moses Hess who was a “revolutionary socialist before Marx, and a Political Zionist long before Theodor Herzl” would die on April 6, 1875 in Paris.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Moses Hess.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Moses-Hess.

↩︎ - Hess, Moses. Rome and Jerusalem. Maisel, 1918. ↩︎

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Moses Hess.” Encyclopedia Britannica, April 2, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Moses-Hess. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess” In Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (Second Edition), 267-316. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400843237-014 ↩︎

- Hess, Moses. Rome and Jerusalem. Maisel, 1918, 56. ↩︎

- Ibid, 166. ↩︎

- Ibid, 165. ↩︎

- Ibid, 63. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, 62. ↩︎

- Ibid, 146. ↩︎

- Ibid, 147. ↩︎