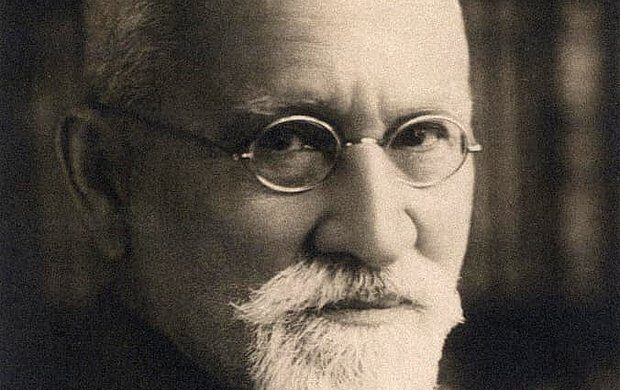

Simon Dubnow: Biography

Born: September 10, 1860, Mstislavl;

Died: December 8, 1941, Riga

Simon Dubnow was a Russian Jewish writer, historian, and social philosopher. He was born on September 10, 1860 in Mstislavl. He descended from a long line of Jewish Rabbis and scholars. Dubnow received a traditional Jewish education, at a heder where he studied the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud. After discovering literature of the haskalah or Jewish enlightenment, he would secretly rebel against his orthodox education by reading haskalah works in secret. He prepared hard for his matriculation at university, yet after failing an exam in mathematics he did not matriculate or make any subsequent attempt to. 1

His failure to matriculate at a university did not stop his efforts in educating himself as he undertook self study in subjects like history and philosophy. He would gain employment at a Russian-Jewish intellectual journal, Voskhod. He also worked as a historian, researching, for example, the history of autonomous Jewish institutions in Eastern Europe. In 1906, he moved to St. Petersburg to take up a professorship in Jewish history at a university until it was eventually disbanded. Dubnow was also involved in politics as he founded the political party Folkspartei. During the Bolshevik Revolution, Dubnow was mortified by their violence and dictatorship, and would eventually emigrate out of Russia with help from friends.2

In his work Nationalism and History: Essays on Old and New Judaism, Dubnow writes about his thoughts on pressing Jewish issues like nationalism, Zionism, and assimilationism. He writes that Jews are a nation saying that “it should be clear to all how greatly mistaken are those Jews and non-Jews who deny to the Jews of the Diaspora the right to call themselves a nation, only because they lack the specific external marks of a nationality which were taken from them or which became weakened during the nation’s long history. Only he who completely fails to understand the nature of the national ‘ego’ and of its development can refuse to accord nationality to this old historic community which, during the last 2,000 years, has been transformed from a simple nation into the very archetype of a nation.”3 He goes on to say that the rejection of Jewish nationhood and nationalism amongst Jews comes from two camps. The religious who believe that Judaism is a religious nation or community and those who fail to adhere to the rules of the religion are as such removed from the community. The other is what Dubnow calls the “freethinkers” which Dubnow says that they are the “assimilationist intelligentsia… see in Judaism only a religious community, a union of synagogues which imposes no national duties or discipline whatsoever on its members. According to this view, the Jew can become a member of another nation and remain a member of the Mosaic faith. He is a German Jew, for example.”4 Dubnow goes on to write that this group is “the invention of naive ideologues, or calculating opportunists, who seek to justify by means of this artificial doctrine their desire to assimilate into the foreign environment to benefit themselves and their children.”5 From his writing, we can see that Dubnow is very negatively polarized towards Jewish assimilation.

In this work, Dubnow writes about a new concept called Autonomism, or Jewish Autonomism. It was based on Dubnow’s thinking on Jewish history of “the course of the development of the national type: tribal foundations, territorial, political, and cultural-historical or spiritual. The transition from material to spiritual culture in the growth of a nation… a test of the full development of the national type comes in the case of a people that has lost its political independence, a factor generally regarded as a necessary condition for national existence… if, despite the fact that the external national bonds have been destroyed, such a nation still maintains itself for many years, creates an independent existence, reveals a stubborn determination to carry on its autonomous development – such a people has reached the highest stage of cultural-historical individuality… we find only one instance, however, of a people that has survived for thousands of years despite dispersion and loss of homeland. The unique people is the people of Israel.”6 He goes on to write that “the chief axiom of Jewish autonomy may thus be formulated as follows: Jews in each and every country who take an active part in civic and political life enjoy all rights given to citizens, not merely as individuals, but also as members of their national groups.”7 Jews are not totally separated from the state they reside in, but have cultural and minority rights. This ideology would play a major role in influencing future Jewish organizations such as the Bund, an anti-Zionist organization against Jewish immigration to Palestine.

Simon Dubnow’s thoughts on Zionism were complex. He believed that Zionism was a reaction to assimilation and antisemitism. He criticized Zionism as a fantasy, “Political Zionism is merely a renewed form of messianism that was transmitted from the enthusiastic minds of the religious kabbalists to the minds of the political communal leaders. In it the ecstasy bound up in the great idea of rebirth blurs the line between reality and fantasy… Political Zionism is thus a web of fantasies: the dream of the creation of a Jewish state guaranteed by international law.”8 He predicted that by the year 2000 only 500,000 Jews would immigrate and live in Palestine, what Dubnow refers to as “our ancient homeland.” However, in a revised edition of his work he writes in 1936 that, “times have changed, and it is our good fortune to have now, 55 years after the beginning of new colonization, an agricultural population of 70,000 and an urban population of close to 300,000. May they multiply further! Despite all this, I did not delete my old estimates, in order that it may serve as a symbol for those days, ‘days of little faith.’”9 He wrote in the 1936 introduction to his revised work that, “notwithstanding my severe objections to political Zionism, I was never opposed to its positive and practical side, the rebuilding of Palestine, but only to its negative aspect, the rejection of the galut [Jewish diaspora]. This was the central point in my long controversy with Ahad Ha’am, the closest to me in spirit among my friends.”10

In 1933, he fled from Germany as a result of the Nazi rise to power, and he rejected calls for him to flee to the United States or British Palestine instead fleeing to Latvia. He was murdered by the Nazis during his deportation to an extermination camp on December 8, 1941.11

- Dubnow, Simon, and Koppel Pinson. Nationalism and History; Essays on Old and New Judaism. (Jewish Publication Society of America, 1958), 8. ↩︎

- Ibid, 26. ↩︎

- Ibid, 88. ↩︎

- Ibid, 90. ↩︎

- Ibid, 90. ↩︎

- Ibid, 80. ↩︎

- Ibid, 137. ↩︎

- Ibid, 164. ↩︎

- Ibid, 164. ↩︎

- Ibid, 54. ↩︎

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Simon Markovich Dubnow.” Encyclopedia Britannica, November 27, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Simon-Markovich-Dubnow. ↩︎