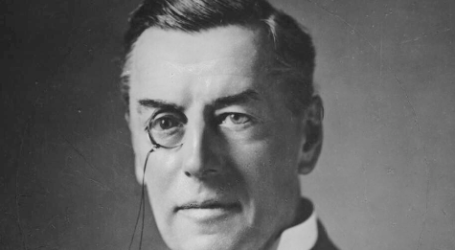

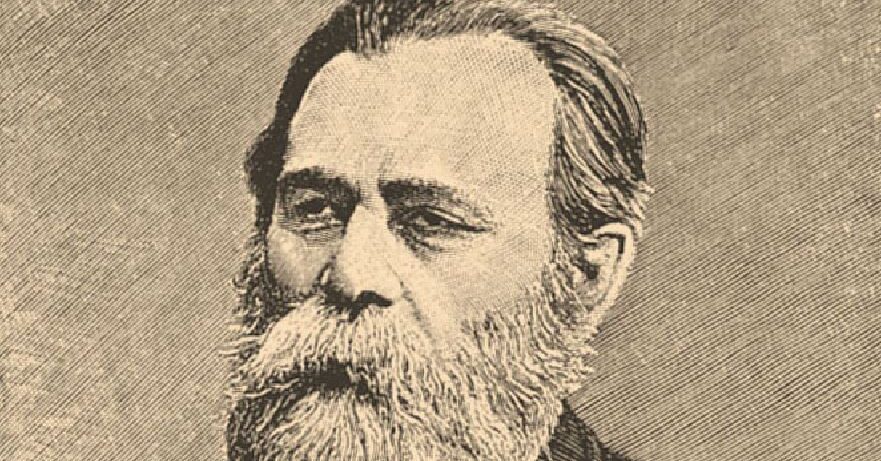

Leo Pinsker: Biography

Leo Pinsker

Born: December 13, 1821, Tomaszow;

Died: December 21, 1891, Odessa

Leo Pinsker also known as Leon Pinsker or Judah Leib Pinsker was born on December 13, 1821 in Tomaszow.1 Pinsker was a doctor, writer, and Zionist activist and leader. His father was a Hebrew teacher.2 Pinsker settled on a career in medicine as a physician. Early on in his life, Pinsker was an assimilationist, even joining the Society for the Promotion of Culture Among the Jews of Russia, an assimilationist organization that promoted the integration of Jews in mainstream Russian society. Pinsker favored a secular education over a religious education and pushed for the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Russian. Throughout his life, he saw many pogroms in Russia such as the 1871 Odessa pogrom, yet it was not until the 1881 Odessa pogrom that he turned against his assimilationist beliefs. In this pogrom in particular, Pinsker believed that the government and intellectual class not only ignored it, but that it was “abetted by the government and defended by the press.”3 Pinsker began developing a national consciousness and turned away from his former assimilationist beliefs and towards Jewish nationalism as a solution.

In 1882, Leo Pinsker wrote his magnum opus titled Autoemancipation. This is considered a groundbreaking and influential work in Zionism. He begins this work by writing about the “Jewish Question” saying that it still has not been solved. Pinsker says that the idea of nation-states melting away and world peace is “still invisible in the distance.”4 He states that while world peace isn’t in the near future, nations can modify their relations with one another suitably based on a mutual understanding and respect, based on treaties and international law. Pinsker states that the nations of the world and the Jewish people don’t have this mutual understanding and esteem, and thus the Jewish Question will remain unsolved.

Pinsker says that the Jews “lack most of those attributes which are the hallmarks of a nation. They lack that characteristic national life which is inconceivable without a common language, common customs, and a common land.”5 Above all, Pinsker says that Jews “are not a nation, because they lack a certain distinctive national character, possessed by every other nation, a character which is determined by living together in one country, under one government. It was clearly impossible for this national character to be developed in the Dispersion: the Jews seem to rather have lost every memory of their former home.”6 Pinsker says that Jews in his day living in the nations of the world “occupy the position of a nation long since dead. With the loss of their fatherland, the Jewish people lost their independence, and fell into a decay which is not compatible with existence as an integral, living organism. The state, crushed under the weight of Roman rule, disappeared from before the eyes of nations.”7

He goes further on to discuss what he calls “Judeophobia” which he refers to as a “psychic disorder.” He claims that Judeophobia is a hereditary disorder that has been passed down through generations. He says that he remains in every country, an alien. He says that emancipation of the Jews that happened in his century is an important achievement, yet Pinsker makes the distinction that while Jews were legally emancipated they were not socially emancipated. He says that nations and citizens of these countries will always have a natural antagonism to Jews and to not ignore this fact and to not complain of it. Instead, to know it and work to “not remain forever the Cinderella, the butt of the peoples.”8

Leo Pinsker writes that the nationalistic aspirations of the Jewish people are more than justified. He writes that Jews “play a more important part than those peoples in the life of civilized nations, and they have deserved more humanity; they have a past, a history, a common, unmixed descent, an indestructible vigor, an unshakable faith, and an unexampled history of suffering to show; the peoples have sinned against them more grievously than against any other nation. Is that not enough to make them capable and worthy of possessing a fatherland.” He goes on to write that the Jewish struggle for independence, “not only possesses the inherent justification that belongs to the struggle of every oppressed people, but it is also calculated to attract sympathy of the people to whom we are rightly or wrongly obnoxious.”9

He then goes on to discuss the location of this nation. He argues that Jews must not “dream of restoring ancient Judea.”10 He argues against creating a land where they were once destroyed and expelled from. Pinsker states that they don’t need an Ancient Kingdom of Israel and Judah but just a land where no foreign masters could expel them from. He says that “perhaps the Holy Land will again become ours. If so, all the better, but first of all, we must determine – and this is the crucial point – what country is accessible to us, and at the same time adapted to offer the Jews of all lands who must leave their homes, a secure and unquestioned refuge, capable of being made productive.”

Pinsker concludes his pamphlet saying that “Jews are not a living nation; they are everywhere aliens; therefore they are despised. The civil and political emancipation of the Jews is not sufficient to raise them in the estimation of the peoples. The proper, the only remedy, would be the creation of a Jewish nationality, of a people living upon its own soil, the auto emancipation of the Jews; their emancipation as a nation among nations by the acquisition of a home of their own… the international Jewish Question must receive a national solution.”11

Pinsker’s pamphlet was very influential. Theodor Herzl wrote in his diary that in 1896 he “read today [Pinsker’s] pamphlet, Autoemancipation… Dumbfounding agreement on the critical side, great similarity in the constructive. A pity that I had not read it before my own pamphlet was printed. Still, it is a good thing I knew nothing of it – or perhaps I might have abandoned my own undertaking.”12 Herzl wrote this around the timing of his publication The Jewish State, a seminal work of Zionism itself showing how important Pinsker’s work was.

Leo Pinsker would go on to work as a Zionist activist, becoming the leader of Hibbat Zion or Love of Zion. Though the organization was lacking in funding, it did succeed in establishing a few settlements in Ottoman Palestine. Pinsker would die on December 21, 1891 in Odessa.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Leo Pinsker.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leo-Pinsker. ↩︎

- Leon Pinsker – Biography. Jewish Virtual Library. ↩︎

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Leo Pinsker.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leo-Pinsker. ↩︎

- Pinsker, Leon. Autoemancipation. (New York, NY, 1882), 2. ↩︎

- Ibid, 2. ↩︎

- Ibid, 2. ↩︎

- Ibid, 2. ↩︎

- Ibid, 13. ↩︎

- Ibid, 13. ↩︎

- Ibid, 14. ↩︎

- Ibid, 23. ↩︎

- Shumsky, Dimitry. “Leon Pinsker and ‘Autoemancipation!’: A Reevaluation.” Jewish Social Studies 18, no. 1 (2011): 33–62. https://doi.org/10.2979/jewisocistud.18.1.33. ↩︎